BAMAs take New York!

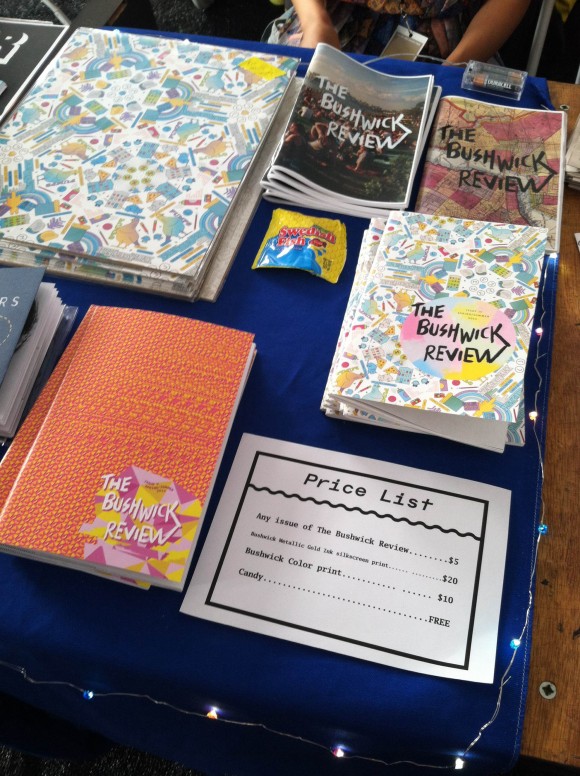

The BAMAs enrolled in English 497A, taught by Charlotte Holmes and Jean Sanders, were lucky enough to take a trip to New York last weekend to attend the NY Art Books Fair at MOMA PS 1. The trip served as inspiration for the art books the students will be making in class.

MOMA PS 1.

Some of the many art books.

“I’d rather be reading.”

BAMAs enjoying the shade in Central Park.

This trip was inspirational and so much fun. We are so grateful for the opportunity!

Seamus McGraw Visit

On Wednesday, September 24, author Seamus McGraw visited Penn State University as part of the Mary E. Rolling Reading Series. McGraw’s 2011 book The End of Country, a memoir/journalistic investigation, explored natural-gas drilling in McGraw’s hometown in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania. But before McGraw read from Country and his upcoming book, due for release in Spring 2015, he asked the audience in Palmer Auditorium a simple question: “what is fracking?”

A girl tentatively raised her hand, offered an answer about wells, water and chemicals blasted into the underlying shale, and gas migrating upward because of the intense pressure.

McGraw nodded, clasped his hands, and proceeded to make an important distinction. One misconception people have about fracking, he said, is they think fracking fractures the ground, forcing shale to move upward through the breaks it creates. In reality, fracking exploits existing fractures within the ground, monopolizing on cracks that have always lurked underfoot. To McGraw, this metaphor summarizes the entire fracking industry: it doesn’t fracture the towns and communities that live over the shale deposits—it just exacerbates problems that have always hidden there, below the surface. He continued to explain that there’s no black-and-white morality when it comes to fracking. Fracking is a process that garners enormous benefits, and one that carries heavy costs. It’s a process about which McGraw hopes American can hold a conversation, a genuine one that embraces the gray area surrounding the social, political, and economic consequences of drilling for natural gas.

Ito Romo Visit

Writer Ito Romo came to Penn State last week to kick off the Mary E. Rolling Reading Series. He’s pictured here at a Q&A in Bill Cobb’s graduate fiction workshop, where he discussed his writing and technique: he talked about the influence of setting, the importance of knowing where to end a story. His book The Border is Burning is a collection of very short stories, all of which take place in southern Texas, right on the Mexican border, and all of which, in Ito’s own words, are pretty depressing. Ito said that he chose to write the stories the way that he did to present people who are marginalized because of their social or economic classes or because of the drug trade in south Texas as very real and very human. He said people often tell him that his stories elicit physical pain, and this was evident when he gave his spirited, jarring reading on Thursday night. His stories are gripping and impossible to forget. We are so lucky to have had such a talented and gracious writer come speak with us!

Welcome Back!

Hello, all, and welcome to the 2014-2015 school year! We think it’ll be a good one.

Remember to check out our blog throughout the year for events, exciting news, and other updates!

Where Did They Go?

This year’s crop of BA/MA graduates are headed into some exciting new ventures.

Kayla Candrilli will begin the MFA program in nonfiictin writing at the University of Alabama.

Laura Dzwonzyk will spend next year in Berlin, Germany as a Fulbright teaching fellow.

Elise Gruber will be working on a literacy project at Penn State.

Nicholas Miller will begin the MFA program in fiction writing at the Michener Center at the University of Texas.

Amanda Stango will begin teaching high school English while working on her MA in English education at Marywood University in Wilkes-Barre, PA.

Two students who graduated in 2013 will also be entering graduate school in the fall.

Jackie Campbell will enter the PhD program in English at the University of Wisconsin.

Rosemary Santarelli will enter the MFA program in fiction writing at Columbia University.

Congratulations to everyone!

Student Showcase: Laura Dzwonczyk

White Gloop Judgment

It was inevitable. I should have known that, one day, I’d receive the bugged-out stare, the strange look, at my face, back down at my sandwich, then back to my face again. Is she serious? Oh god, she’s really serious. That’s what she’s eating. Alas, I was a sheltered child, encouraged by overly generous parents to pursue “individualism,” another word for, “we’ll let you eat whatever the hell you want, in whatever combination, as long as you’re eating something.” And so my mother said nothing when I first made up my favorite sandwich, didn’t bat an eye. My father may have made a few wisecracks, but he jokes about everything, so it went right over my head.

And so I didn’t give my culinary choices a second thought until the winter I was six. My neighbor Kaitlyn and I had been out sledding all morning, and when we returned to my house for lunch, my mother was making soup and sandwiches. As I sat myself into my kitchen chair, sitting on my legs so I’d be high enough to reach the table, I saw Kaitlyn look with half-interest, half-disgust at my lunch.

“Is that a mayonnaise and cheese sandwich?”

“Yep.” I was unperturbed. I hated any type of lunchmeat, and mustard just wasn’t my thing, but this right here was heaven on earth: two slices of white American cheese slathered with mayo, all slapped haphazardly between two pieces of white bread. Lunch of champions. “Do you want one?”

She shook her head, with that unconditional acceptance that pervades childhood, reaching for her own turkey and cheese. I continued to pack this lunch all throughout my elementary school days, alternating it with Lunchables, unaware and uncaring of any outside opinions. This same attitude allowed me to wear overalls and flowers in my hair and read preteen historical fiction novels like Boston Jane for SSR time and skip down the halls with my friends after recess, singing “It’s No Fun Being in Sixth Grade” at the top of my lungs. It was only after my move to middle school that I abruptly started picking out jean miniskirts, shaving my legs after Jordan Munsell came up to me during softball day in gym class and said, “Everyone is making fun of you,” and eating lunch meat. Unsurprisingly, I still do all of these things.

“We need to get you back to where you were before middle school,” my shrink said after our initial meeting. When I looked at her in horror, she laughed. “Your mindset, I mean. How unfiltered you were, how much you let other people see your true self without letting your brilliant mind get in the way.”

When it comes to debate over my favorite condiment, I’m a surprisingly good mediator. I can completely understand why it scares people, with its semi-gelatinous, gloopy off-white manner. I sympathize with people who are put off, even repulsed, by its strange, thick, barely-there flavor. But as much as I want to go along with everyone else on this one, as much as logic defies it, I can’t quit mayonnaise. It raises sandwiches and burgers a cut above their normal standard, and don’t even get me started on pasta salad. I’d probably be model thin without it, but avocado spreads and ketchup just don’t do it for me. It has that strong of a hold over me. It’s magic. And so, when you tell me you don’t like mayonnaise and I calmly, politely, ask you to please never speak to me again, it’s nothing personal. I don’t actually mean it. But I may love mayonnaise just a little bit more than you.

Student Showcase: Alaina Symanovich

Stains

As a girl you feared dropping the communion tray more than anything. Not the one with the wafers, of course, but the wine tray, the one with the million thimble-sized cups that glittered up at you like galaxies. You imagined the disaster unfolding as your pastor shouted the blood of Christ, shed for you: the tray tumbling out of your hands, flooding your Sunday clothes with the million sips of wine and ruining the seat and the carpet and the communion service. Even when your parents admitted that the tray carried only Welch’s, nothing stronger, you still fretted, still thought if Jesus could turn water into wine then surely He could infuse sacred things into a plastic bottle #7.

Maybe you should have dropped it, you realize now, staring at the broken glass that constellates the ground. Maybe you should have bathed in the blood of Christ, watched it pool in the crooks of your elbows and trickle down your legs and seep under the arches of your feet. Maybe then the stain would have stuck, would have purpled your insides, would have made you faithful. Jesus said if anyone thirsts, let him come to me and drink, and you think Jesus didn’t understand how much drink you required. I’m sorry, Jesus, you should have told Him. I need too much. I’m more indulgent than I like to think.

You never dropped the communion tray, though, so here you stand. Here you stand with glass around your shoes, shaking your head and apologizing for the shattered bottle. I must be a little drunk, you tell your friend. He wants to know how much beer you wasted and you can’t remember. You remember a skinny brunette, someone-from-somewhere’s little sister, pointing to the lower fourth of the bottle and saying you wouldn’t get drunk until you got there. You remember another girl warning you not to get there. You remember swearing you would, your friend raising his bottle and shouting fuck her she’s not the god of you and you laughing and telling him I’ll finish it, I’m finishing it, alright.

You dropped it. You glutted yourself with it and still couldn’t finish, too much you’ll realize the next morning; less than you wanted but more than you could handle. You fail at gluttony, fail at filling the empty space inside you. Whether you shoot Welch’s thimbles or shoot for the lower quarter of the bottle you can’t fill the void—evidenced by the sloshing in your stomach because full things don’t have wiggle room and the sloppiness of your words because they run away like prodigal goddamn sons and the slowness of drunk tears because every. fucking. time.

Sometimes you feel like the only empty person in the room, the only one who can suck down so much juice and alcohol and even—you remember why your mouth tastes like a campfire—cigarette smoke and not think, voila!, here I am!, this is my color! You are an empty glutton, trying to fill yourself in but only making a mess. So you smile at a boy until he hands you his beer, hoping against hope that this drink will be the one that stains.

Student Showcase: Nick Miller

Electric Nothing

Inside the house with the red door, Oliver sits in lowlight counting the take out loud. Each bill he skims off the stack and sets onto the table, calling it by its name. Twenty, twenty, fifty, ten. He makes marks in a notepad, impulsively crossing out old figures and re-adding the sum. Cigarette smoke wafts from the cracked bathroom door. From time to time, when the hairdryer clicks off, he can hear Leslie singing. Since the latest concussion she sings always. At first he was very afraid. She’s mostly back now even though from time to time there’s trouble doing one thing for too long and she still hasn’t been back to work at the pet shop. The singing is a good sign though. When she remembers entire verses, Oliver feels soothed like above him the sky is completely empty and nothing is blocking him from the way-out-there everything-else. He’d teased her the night they unloaded the knifefish into the tub that, when Chance bucked her off last, she must have landed on a ringing rock. It must’ve busted song into her skull. Her voice sounds like the things he thinks of when he says her name or just rolls it over his tongue. Leslie, velvet, wine, smoke. Soft things like clouds. Out the window behind him, an unbroken one hangs over building tops, and, when he looks up, Oliver can see its featureless reflection across the fish tank.

He feels a quiver in his chest each time the leftmost digit goes one higher. When he adds an extra zero, he remembers his grandfather who died of a heart attack at thirty. He sums up the final figures, slips two hundred into his wallet, and tucks the rest into a box labeled Freshwater Salts. Tonight they’ll do it all: deep fried pickles or calamari to start, he’ll get a steak, each their own dessert, and drinks the whole time. One splurge he can afford. He senses, looking into the white haze on the tank glass, a splurge they desperately need.

He runs his hands through his hair. A fish tank is a thing of delicate balance. There’s inhabitant type, biotype agreeability, ph, lighting, filtration, salt water and fresh, predator and prey. In the same notebook he has scrawled definitions of aeration and oxygenation. Species too aggressive or too foreign can lead to stress-death. Oliver wrote it down when the leader of his night seminar said, “Electricity won’t flow through the endoskeleton and their hearts will stop.” At night, when Leslie pinches food into the tank, he holds her by the elbow and makes sure she doesn’t add too much. Together they watch fish with round mouths pluck flakes from the surface.

Another two days, with luck three, before the fish start to belly up. Horace is driving down from Missoula with a couple tanks and contacts for buyers. He’ll need Horace to help him drain it, to get the Tiger Barbs away from the Swordtails and Angelfish, to get the Shortfin Squid out. The squid are too active, darting in and out of the hairgrass like ducks fleeing a birddog. The real work will be with the Moorish Idol. It’s quick as lightning and easily stressed. Oliver worries about this fish, with its long black barbels, yellow spotted lateral line and dorsal. It’s a heavily-decorated and arrogant beauty. Worth three times as much as the others.

Half of the take will go to supplies, the rest to bills. He needs to stock up on tanks to spread out the fish and sell, some filter types, more water conditioner. Maybe even some polo shirts with a name printed over the pocket to look real. If she can, Leslie will help him come up with a name. She had talent of that sort. The only woman who could do her hair with two knifefish in the tub. The fish are nocturnal and soon will start to squirm.

Oliver gets up and walks to the bathroom. He takes the cigarette out of the tray and puts what’s left between his teeth. Leslie in her pick robe sits at the edge of the tub, reaching toward the water.

He rushes her, grabs her by the wrist and pulls her from the tub. His cigarette falls to the floor.

“Gymnotiforms are electric,” he says. Her face is heavily made up, birchbark pale with outlined lips, cat eyes drawn on.

She looks back at him confused, her razor eyebrows pressed.

Oliver loosens his grip on Leslie’s wrist, and places both her hands on his hips.

“I don’t want the fish to hurt you,” he says, stepping the cigarette into the tile.

Her lip quivering, she nods up at him.

“Okay, Oliver,” she says. “I won’t touch your fish.”

He holds her there for a minute, gently, then tightly, so tight that her white make up smears wet against his shirt as she presses her fingers into his back and in the tub the knifefish know that it is night and begin to stir and if he holds her there long enough running his hands through her hair Leslie will begin to sing and he will see the muscly black bodies of the knifefish jostle in the tub as if it is not a tub but a wide cold river in Argentina woven between mountains so tall that, if you got to the top, your hands could cup lightning and you would be as much part of the sky as of the earth.

Student Showcase: Kayla Candrilli

Faggots

Fairies, faggots, fairies. I believe in fairies, have ever since Peter Pan. Tinker with this, tinker with that. Break the line no matter the cost. The way their wings spread, eagles the size of my thumb—heads platinum blond—or white? The way they live in the pock marked trees—little screech owls that don’t screech but sing musical numbers off Broadway: Wicked, Sweeny Todd, Hair, Hair, Hair!

If I’ve learned anything, I’ve learned that most people don’t believe in fairies. They never did. The fairies flew around too far outside the sphere of white angels and fat cherubs. Maybe it’s because Fairies are unisex, androgynous the way a hummingbird might be (as they never slow enough to see—to know for sure—amphetamine addicted beauties). There’s no little cherub penis giving it away, no shawls of Toole meant to cover young, prepubescent breasts.

All fairies come from the Great Fairies of ancient times: Alexander the Great, Sappho, Plato. They, spawn of the greats, mischievous and diabolical, always get their way, unless a nonbeliever sees them sparkle, hears them sing. Faggots, maggots. Strung up by their faux feather wings, tangled in barbed and electric wire. Currents shocking their bodies to convulse like any Cher song from the 80s. All the world is made of faith, and trust, and pixie dust.

Still on the streets at night (so long after reading them into existence) I see them sparkle, stumble. Drunk fairies. Sometimes (most times) I’m one of them, checking my reflection in dark storefront windows, to ensure I’m still shining, to know my wings are beating as fast as they should, as fast as my speeding heart, catching and throwing the yellow lights of street lamps like kisses. Little narcissists we are, fairies, faggots, pouring glitter over ourselves like holy waters.

You must be logged in to post a comment.